Like a Hawk

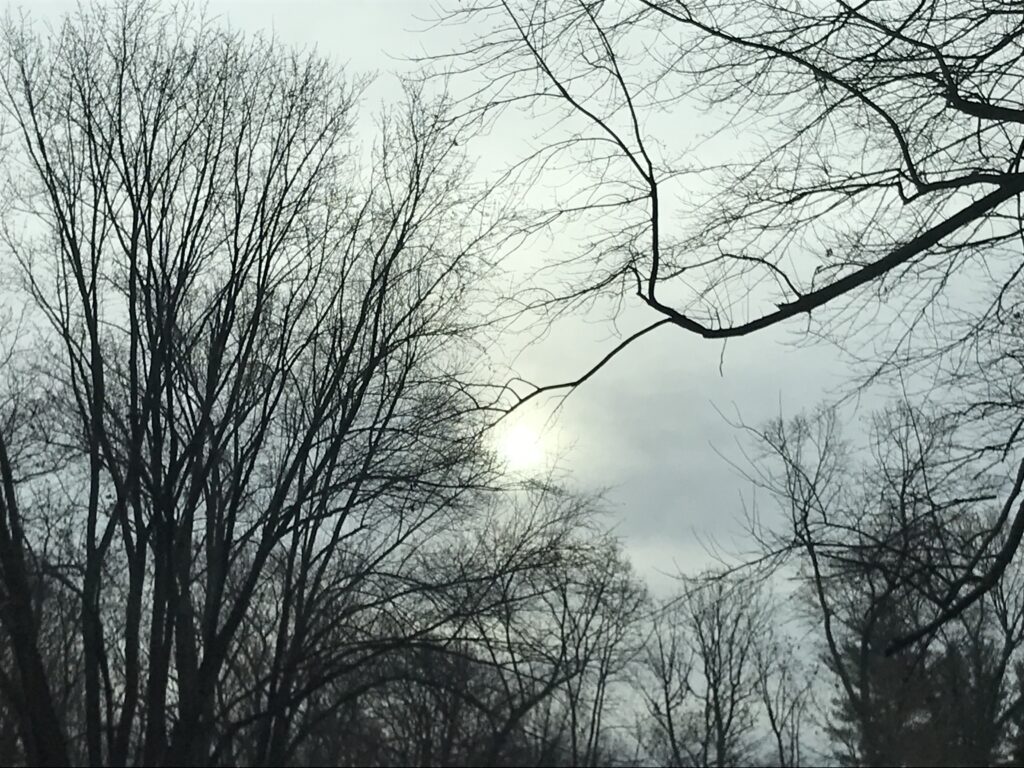

The small birds of winter are much on my mind, the sparrows and chickadees and downy woodpeckers, in part because it is winter and in part because a new suet block has them flocking to the deck.

The large birds of winter have found their way here, too. Which drives the small birds away. If you’re looking for an avian party-killer, just invite a hawk to lunch.

This robust fellow showed up yesterday, as I was munching on a salad. I knew he was looking for the meat-eater’s special so I kept my eye on him as I finished my greens.

The hawk was seeking prey, of course, watching the small birds like a … well, like a hawk. But he wasn’t the only one laser-focused yesterday. While he was watching the small birds, I was watching him.