The Toughest Job You’ll Ever Love

Now that I’ve visited Suzanne in Africa I can attest to this slogan. Peace Corps volunteers do not live lives of luxury. Many of them settle in villages without running water or electricity; they get around on foot, bike, moto or bush taxi; they eat a lot of rice and beans.

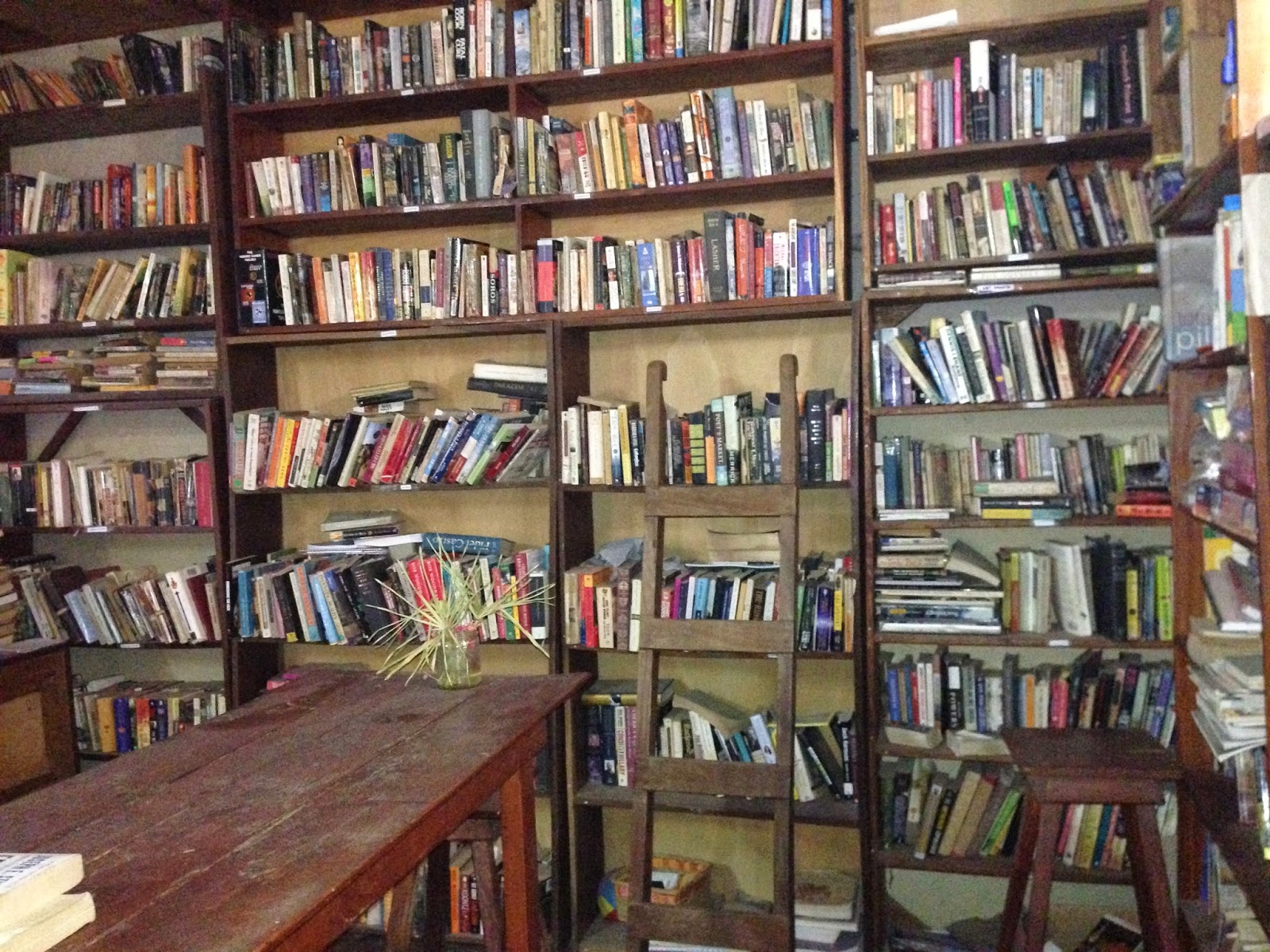

But their lives are rich in time and, surprisingly, in books. I visited two Peace Corps work stations with libraries to die for. One even had a ladder to reach the topmost shelves. There was a sizable collection of fiction (I read Purple Hibiscus by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and was plunged into the world of a young Nigerian girl), a rich travel section (I picked up a crazy little book called The Emperor of Ouidah by Bruce

Chatwin and devoured it a few days before we visited Ouidah ourselves), even non-fiction and memoir (I read Infidel and Nomad, both by Ayaan Hirsi Ali).

I already knew from Suzanne’s experience how much she’s read the last two and a half years, and other volunteers said the same. But the greatest proof is this: I read eight books in less than three weeks. It would take me three months to read that many books at home.

Of course, I was on vacation, I took long bus rides. All of this is true. But something else is true, too. I had scant Internet access. And books, shelves and shelves of books, flowed in to take its place.