20 Years!

I learned early this morning that today is the 20th anniversary of Wikipedia. That I learned so early is noteworthy, I think, a sign of how much I rely on something I once thought was faintly ridiculous.

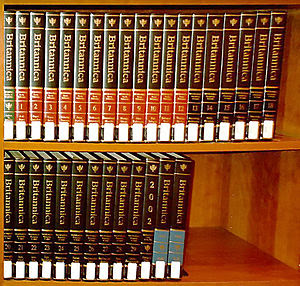

A crowd-sourced encyclopedia? What of the scholar laboring in his or her attic (and let’s face it, it was usually a “his” back in the day)? What of the World Books lining the shelf?

Through the years I’ve learned a little about the standards of Wikipedia, which, though odd, can sometimes be rigorous. Let’s just say that if you submit a PR-like entry, they will come after you.

Plus, I’ve become lazy. I spent many years doing research in libraries, and I love the older style of knowledge acquisition. But I’ll admit, it’s pretty amazing to have such a compendium at my fingertips.

So happy anniversary, Wikipedia! And thank you for your service!

(Photo: Wikipedia! And that’s another reason I love them. I can use their photos without fear of copyright infringement.)