Morning of Words

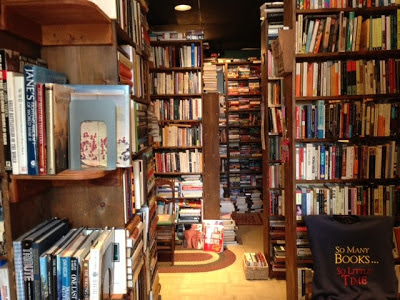

It’s a quiet morning, the stock market is tanking, the government open again after a five-hour shutdown during the night, and I sit here perfectly content with my books, journal and laptop. Not that I’m living in a bubble or anything!

But truly, what can you do? We live in concentric circles, do we not? And when the outer orbits are caustic or frayed, we pull inward, to what makes us happy, what makes us whole.

What’s making me happy now is reading Ursula Le Guin’s No Time to Spare: Thinking About What Matters (2017). I was going to say it was her last book, but am glad I checked. Looks like there’s at least another one coming out.

Here is a passage I marked to copy later:

I know that to me words are things, almost immaterial but actual and real things, and that I like them.

I like their most material aspect: the sound of them, heard in the mind or spoken by the voice.

And right along with that, inseparably, I like the dances of meaning words do with one another, the endless changes and complexities of their interrelationships in sentence or text, by which imaginary worlds are build and shared. Writing engages me in both these aspects of words, in an inexhaustible playing, which is my lifework.

Words are my matter—my stuff. Words are my skein of yarn, my lump of wet clay, my block of uncarved wood. Words are my magic, antiproverbial cake. I eat it, and I still have it.