Frontier Learning

I’m just starting Wallace Stegner’s Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening to the West and am captivated by Stegner’s observation of the haphazardness of learning on the frontier.

I knew books were scarce; teachers, too. But Stegner riffs on this “homemade learning” and how boys (and they were mostly boys then, of course) were often captivated and bent by the first man of learning (and they were mostly men then, too) they encountered.

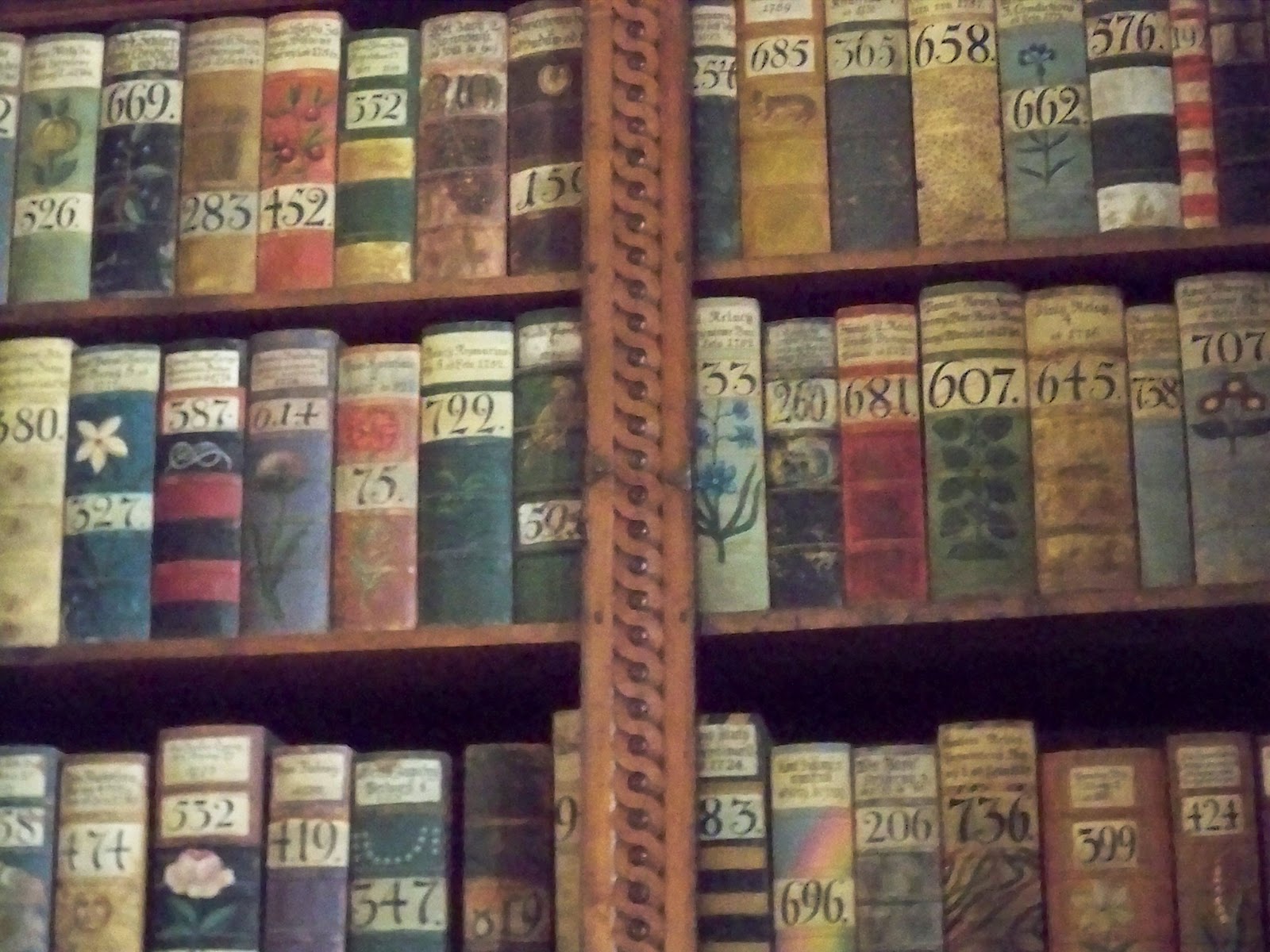

The closest books Abraham Lincoln could borrow were 20 miles away — and they belonged to a lawyer. The closest books John Wesley Powell could borrow belonged to George Crookham, a farmer, abolitionist and self-taught man of science. Crookham collected science books, Indian relics and natural history specimens.

So “[w]hen Wes Powell began to develop grown-up interests, they were by and large Crookham’s interests,” Stegner writes. Powell went on to explore the Grand Canyon and to champion the preservation of the West — all of this with one arm; he lost the other in the Civil War’s Battle of Shiloh. (Powell was a major with the Union forces.)

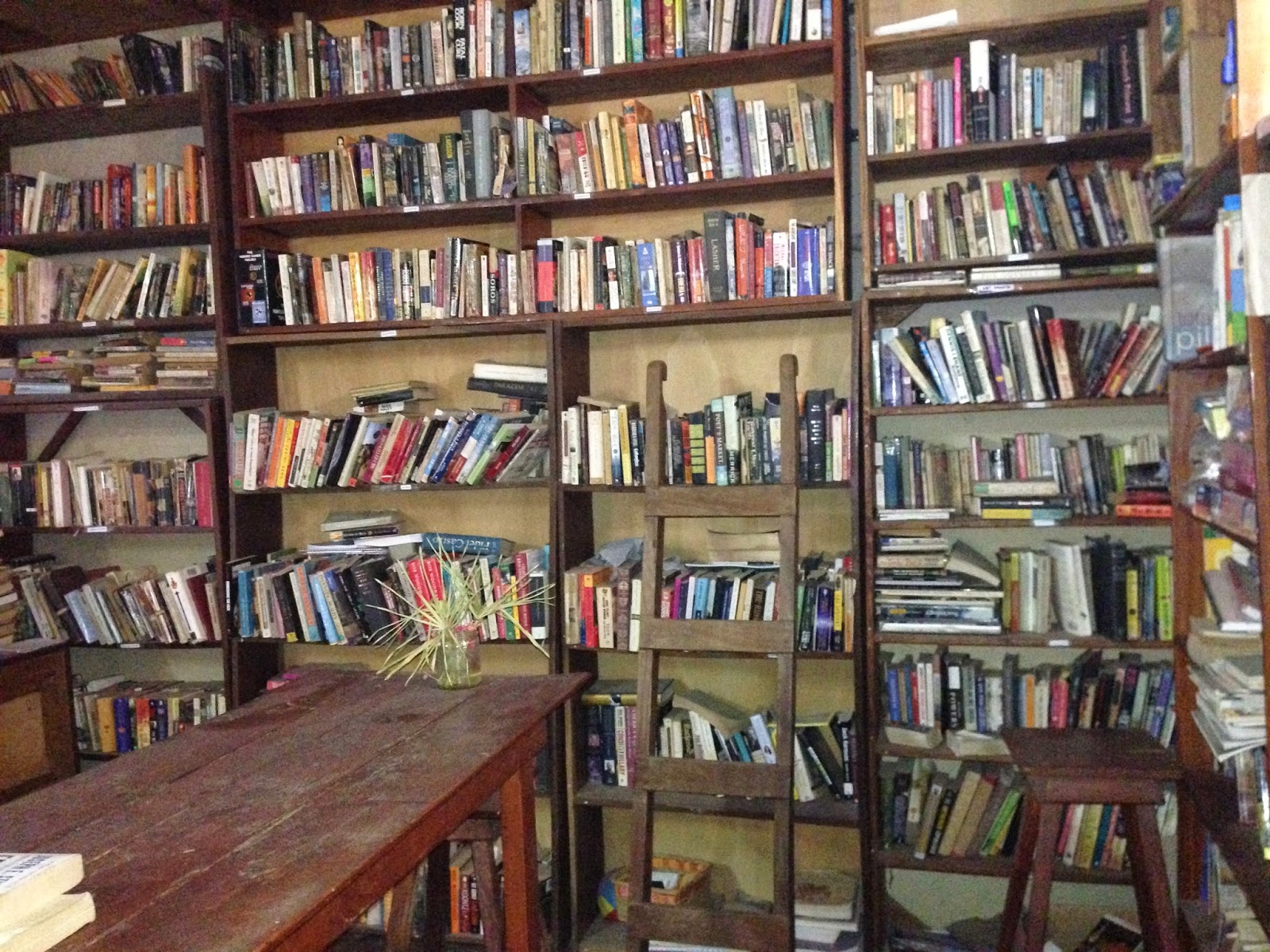

I think of us now with more influences than we know what do to with. Libraries at our fingertips. Information bombarding us day and night. Would we climb on a raft and venture down uncharted waters? Well, I know what I would (not) do. How about you?