Bookmark Revolt

I noticed the telltale threads last night. There was one on the nightstand and another among the bedcovers. No doubt about it, my bookmark was shedding, losing its jaunty tassel. The store-bought item made of laminated pressed violets and violas — such a lovely way to mark my place in the latest journal I’m keeping — is going rogue.

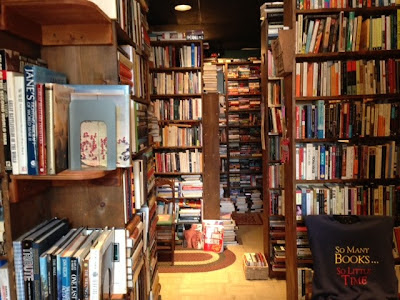

I’m not surprised at these shenanigans. The bookmark is plainly not pleased with an essay I just wrote, the essay in which I disparage store-bought bookmarks and mention how seldom I use them. In fact, I’m only using this one because my current journal does not have its own built-in bookmark.

I could repair this marker. I could collect the slender threads and attempt to reattach them. But since I spent much of yesterday tied in knots (see below), I’m unlikely to do that today.

Does a bookmark know when it’s been thrown under the bus? Apparently, it does.