Dear Friends

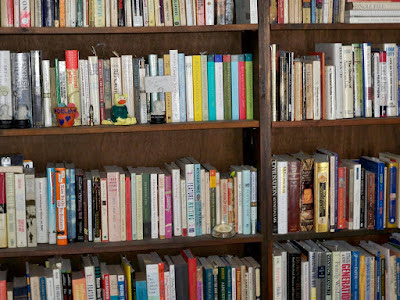

Whenever I write a post these days I’m never far from a shelf of books. This was not the case when I worked in an office and would scramble to put some words down before my day officially began. Now I post at home, and there are walls of books throughout my house.

I wonder sometimes what a younger person might say about these rows of books. My own children don’t count; they’ve grown up here. But someone else, someone efficient and technical who’s quite aware (as am I) that most of these books are available in digital or audio format and that in those formats they would take up a lot less space.

Would they understand why the books themselves, the tattered covers, broken spines, dogeared pages, are so precious to me? Would they get that the books somehow become the ideas, characters and worlds they represent? Would they know how it feels to look to the left, as I’m doing now, and see not hundreds of pounds of paper and acres of felled trees, but a collection of dear friends?