Farewell to Eternity

The reasons we read a particular book are as various as the books themselves, but there are some general trends: a friend recommends it, the book group schedules it, we’ve read a good review of it and — my new excuse — the professor puts it on the syllabus.

The reasons we give up on books are also legion: it doesn’t live up to the recommendation, it’s wicked long, the topic is arcane, the reviewers were wrong. Sometimes a book simply doesn’t fit into the time I have to read it, though truth to tell that seldom happens. In fact, I don’t give up on a book lightly.

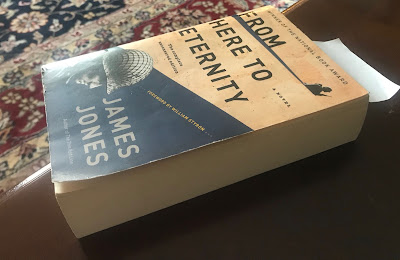

But when I find myself on page 80 of an 800-page novel, when I recall the rather flimsy reasons for picking it up — a friend told me decades ago that she enjoyed it and memoirist Willie Morris speaks fondly of the author, James Jones — and when I realize that I’m already on the line for reading I might not enjoy for the class that’s starting next week … well, then I give myself permission to put it aside. And so, farewell to From Here to Eternity.