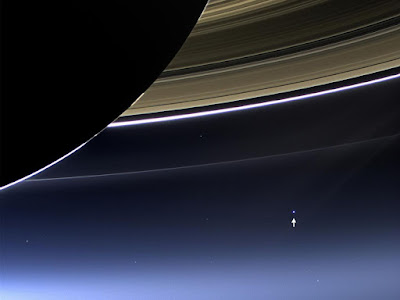

Earth from Saturn

When the children were young and studying the planets, Suzanne decided she didn’t like Saturn. “It’s a show-off, Mom,” she said. All those rings, you know.

I’ve been thinking of Saturn the last few days as images of it were beamed back by the spacecraft Cassini, which plunged into the planet’s atmosphere on Friday, ending a splendid 20-year mission.

For decades Cassini has been enlarging our knowledge of the solar system, taking us to Saturn’s cool green moon Titan, and, with its Huygens lander, actually touching down on the moon’s rocky surface. Cassini discovered plumes of water vapor spouting from another moon, Enceladus, and made many other discoveries.

And then there were the photographs Cassini sent back. The rings and moons and other planets. My favorite is the NASA pic I’ve reposted here. Earth is the tiny speck on the lower right-hand side of this photo. Beautiful, yes — and very, very small.