I’ve loved maps since I was a child. I grew up with a mother who would eat her lunchtime sandwich and pickle while looking at a map, feeding her body and her soul at the same time. I’ve done the same off and on through the years (minus the pickle).

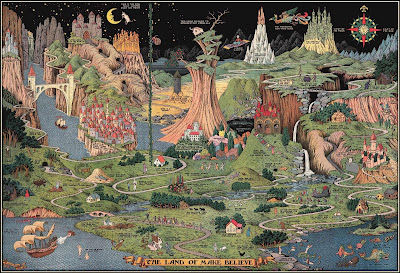

If I were to write another book, I’ve long hoped it would be the kind of book that would have a map in its frontispiece. I had no idea that so many others felt the same way. Enough to fill an entire book, The Writer’s Map: An Atlas of Imaginary Lands, edited by Huw Lewis-Jones.

I found this book on my last trip to the library March 15, and since I’ve not yet had to return any of those books, I’ve had plenty of time to savor this one. In it, authors from Philip Pullman to Robert McFarlane wax lyrical about the book maps that inspired them and the books they’ve written because of them.

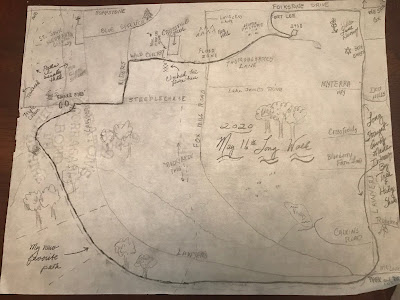

“A map helps to make an imaginary place real. The more detail you put into your beautiful lie, and the more you base it on things that are true, the more it comes alive: for you and for your readers,” says Cressida Crowell in one of the book’s essays called “First Steps: Our Neverland.”

Crowell sees maps as story starters. “When I draw the map of my imaginary world, it will tell me the direction I want to be going in, even when I don’t yet know it myself.”

I’m starting my own map soon.

(Photo: The Land of Make Believe from The Writer’s Map by Huw Lewis-Jones.)