Sheep May Safely Graze

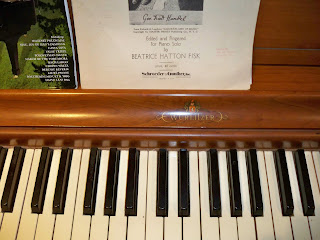

My piano is an old love, a dusty, overlooked and abandoned love. But reading Leon Fleisher’s book (see April 14 post) made me seek out the piano again, the rent-to-purchase spinet that my parents bought for me to learn on and then gave me when I had a house of my own.

I had watched Fleisher play “Sheep May Safely Graze” on YouTube last week. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VzLYxiLNJj8 It was sublime — and even more moving because you could see his little finger curl up after striking the high notes. You could see the effort it took him to play this piece.

I did something impulsive. I ordered the sheet music. And when it arrived yesterday I took it right to the piano. I’ve always loved this Bach cantata, even had a string quartet play it at our wedding. It is sweet and simple, with a melody that wanders off a bit, like a lost lamb. The piece starts off easily enough, but by the second page there are intricate fingerings. You must bring out an inner melody amidst scores of other notes — not easy for someone who’s been doing a lot more typing than playing the last few decades.

Still, I vow (and I vow it here, in a semi-public place!) to learn “Sheep May Safely Graze.” To prepare each part separately. To take it slowly enough that the notes enter my hands and my head. To increase speed only when I’ve mastered the voicing. To bring that lamb home. To play again.