Entertainment in a time of coronavirus: We need it, though we may be a bit reluctant to speak of it when the death numbers keep rising and the photo above the fold of today’s Washington Post is of a stack of caskets in Italy.

Nevertheless, entertainment is helping many of us make it through. The Netflix servers (if they have servers) must be groaning from the load these days. And the same for Amazon Prime and Hulu and of course all the cable news stations, especially the news and movie ones.

I began to watch a show called “Pandemic,” a Netflix documentary. It was made last year but is so spot-on in its depiction of what’s happening now that it’s worth watching for that alone. But I decided last night to try something different, and watched “A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood,” a movie about Mr. Rogers and his relationship with a cynical journalist.

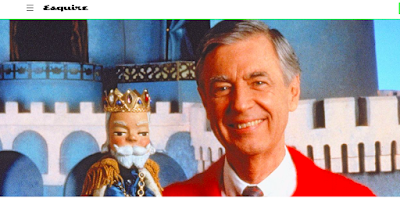

Turns out, there really was a cynical journalist. He really did write a long article about Mr. Rogers in Esquire magazine, and he and the journalist really did become friends.

Interested in how true-to-life the movie was, I read an article on its accuracy. It pointed out the differences, and also said that we don’t see enough of Mr. Rogers, that we don’t learn enough about his life. I saw the documentary about Mr. Rogers and found it boring, as I found Mr. Rogers (though my kids did not, and that’s what mattered).

But the movie’s story about Mr. Roger’s effect on others touched and inspired me. We see Mr. Rogers stooping to talk with a boy with cancer and assure him that he’s strong on the inside. We see Mr. Rogers swimming and Mr. Rogers praying for the people in his life, saying their names one by one.

I took from it a simple truth: that there is always hope and that we must help each other. Not a bad message in a time of coronavirus.

(Photo: Screenshot of the Esquire cover from the 1998 article by Tom Junod. The film also contains a great scene of magazines being printed that I loved, being an ink-on-paper journalist at heart!)