“How long till Tucumcari?”

“Why is it so hot back here?”

And … “Can you turn up the radio?”

These aren’t my children’s comments about long-distance travel; they’re my own. Or at least what can I remember of the cross-country travel my brothers and sister and I took as kids.

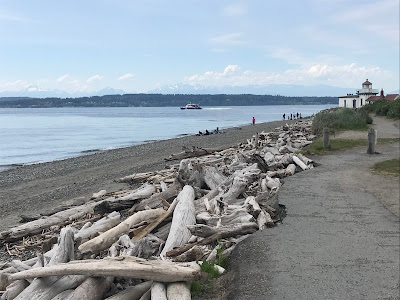

We were stuffed into the backseat and nether regions of the old “woody” station wagon and driven more than two thousand miles, from Lexington, Kentucky to Hollywood, California, and other western destinations. The view out our windows was priceless: forests and grasslands, mountain and prairie, red rocks and cactus; the whole continent unfolding before us. And the soundtrack of our travels? AM Radio.

That’s going to change soon, according to a report in the Washington Post. Some automakers are already omitting AM Radio from their electric vehicles’ dashboards. And Ford is eliminating AM radio entirely.

There have been protests from station owners, first responders, listeners and politicians of all stripes (it’s a rare bipartisan issue), saying that the move may spell the end of AM radio entirely.

I don’t listen to much AM radio — until I’m on a long-distance car trip. And then I tune into these staticky stations to catch the weather, oldies and talk. AM stations give you a taste of the places you’re driving through. I’m sorry to hear that, like so much that is local and authentic, they’re endangered, too.