Remembering Dad

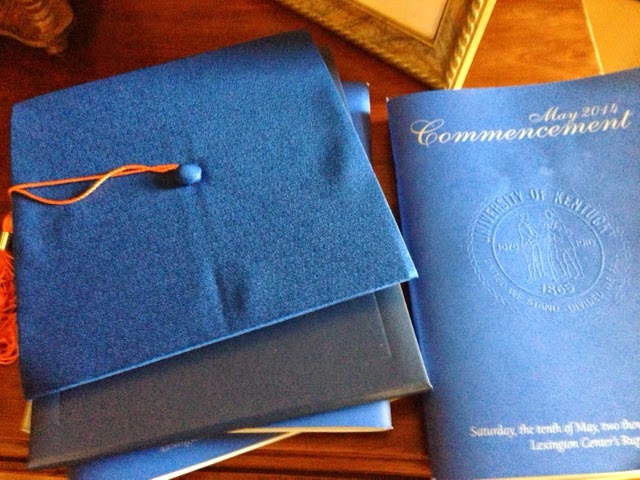

Today would have been Dad’s 91st birthday. And I’ve been seeing him everywhere. In the graduation celebration we just had. In the new spring leaves. In the finally warm, “not-a-cloud-in-the-sky” day.

Where I’ve not been seeing him is in the arm chair where he used to read. Or the corner of the couch where he sat to watch TV. Or the McDonald’s where he hung out with his coffee buddies. It’s still a shock that he’s not in all those places, not alive and laughing in the world.

“Come on, Annie,” he’d say to me during episodes of childhood drama. “You’re living your life like it’s a Greek tragedy.” At the time it bothered me. Did he not appreciate the full implication of having bad hair on picture day?

Somewhere along the way, of course, I realized that he did. But he also knew how to swallow hard and move through life’s sorrows and disappointments. He knew how to make the best of things. It’s a valuable skill. One I’m nowhere near mastering.

Luckily I have his words and his example. And I think of them often — especially today.