Vienna Walk

I found myself in Vienna last Friday. Not Vienna, Austria (though that would have been nice) but Vienna, Virginia, which is 20 minutes from my house, a place I often pass through on my way to somewhere else.

There is a strange disconnect to walk along streets one usually drives, sort of like flipping a video from regular play into slow-mo.

There is the house on the corner lot with its split-rail fence and funky upstairs addition — but instead of zipping by it I can see the details, the little upstairs deck with its wrought-iron tables and unmatched chairs.

There are streets whose names elude me at 35 miles per hour: Garrett and Malcolm and Holmes. Solid middle-class names, though their neighborhoods are ones made pricey by their (mostly) large lots and desirable location within walking distance of Metro (back when that mattered).

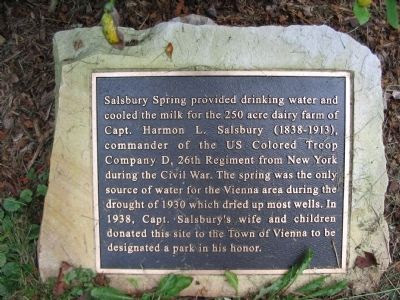

I ambled along Center and Lawyers, past Salsbury Spring, which was the only source of water for the area during the drought of 1930. I saw the place with new eyes after learning that, felt a little more connected to this place I (almost) call home.